Introducing tokka-bench

A comprehensive evaluation framework for comparing tokenizers across human and programming languages.

Table of Contents

- Technical Background

- How Tokenization Affects PretrAIning

- How Tokenization Affects Inference

- Evaluating Tokenizers with Tokka-Bench

- Per-Language Metrics and Results

- Vocabulary Metrics (Aggregated across All Languages)

- Bonus Section: Programming Languages

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgements and References

- Future Research Ideas

View Raw (for LLMs)

(In a hurry? Visit tokka-bench.streamlit.app)

Several months ago, I began working on a new project in my free time — pretraining a small, multilingual LLM. As quests tend to do, mine wandered, and I became very interested in one specific aspect of model training: tokenization.

Today I want to share a framework for evaluating tokenizers, but also explain how tokenizers can help us understand:

- What data sources a given model may have been trained on

- Why some LLMs (especially proprietary models, like ChatGPT, Claude, and Gemini) perform vastly better than others at multilingual tasks

- Why Claude, Gemini, and GPT 4o onwards have closed-source tokenizers

- Why some OSS models are better than others for fine-tuning

Technical Background

Script Encoding & Grammar

Understanding tokenization starts with understanding how text is encoded at the byte level. All language is encoded with UTF-8, but different scripts require vastly different numbers of bytes to encode the same semantic content. English averages just above 1 byte per character, making it incredibly compact. Arabic needs 2+ bytes per character, while Chinese can require 3+ bytes per character to properly encode.

Beyond encoding efficiency, languages have fundamental grammatical differences that affect how information is packed into words. Synthetic languages will pack a lot of syntactic information into single words. For example, I speak Czech, where a phrase like "vzali se" would translate to "they married each other" in English. This grammatical density makes it difficult to compare encoding efficiency.

Tokenization

LLMs don't operate directly on bytes — they operate on "tokens", which are like symbols corresponding to groups of bytes. Most modern tokenizers use Byte Pair Encoding (BPE), starting with individual bytes and iteratively merging the most frequent pairs to build up a vocabulary of subword units.

There are some alternative approaches like the Byte Latent Transformer, but so far they haven't really taken off yet in production systems.

The technical decisions in tokenizer design are numerous and consequential:

- Do you add prefix spaces? (So the "hello" in "hello world" and " hello world" are tokenized the same?)

- Do you disallow byte merges across whitespace boundaries? What about across script boundaries?

- Do you use an unknown (UNK) token or fallback to bytes when encountering out-of-vocabulary sequences?

Hopefully this helps you understand Karpathy’s classic post on tokenization:

How Tokenization Affects PretrAIning

The relationship between tokenizers and pretraining data creates a complex web of effects that fundamentally shape model capabilities. Tokenizers are often trained on the pretraining data of the LLM they will be used in, but different languages get different levels of "coverage" in the tokenizer vocabulary.

Let’s take an example: Khmer. Since Khmer has fewer online resources, less of a tokenizer’s vocabulary will represent decodings into Khmer than English. This coverage disparity means that encoding the same number of words in Khmer will require many more tokens than English. But here's where it gets problematic: pretraining often uses proportional splits of different languages based on token count. This means that you might train on 10 million tokens of English text and 1 million tokens of Khmer, hoping to have a 10:1 ratio of content. But the Khmer text actually represents way less than 10% of the words compared to the English text!

The semantic implications are even more severe. Khmer tokens, because there are fewer, are more likely to represent letters or consonant pairs rather than whole semantic units. This means that models can't "store" concepts, attributes, definitions, and other semantic knowledge in embedding vectors quite as easily for underrepresented languages.

There's a vibrant open-source community making fine-tunes of OSS foundation models for smaller languages. If your tokenizer doesn't handle foreign languages well, fine-tuning will be more difficult and probably require extending the tokenizer with custom tokens. On the other hand, introducing "partially-trained" tokens (tokens that won't show up in the pretraining data) can confuse the LLM and even allow for "token attacks."

How Tokenization Affects Inference

The tokenization disparities that emerge during pretraining continue to create problems during inference. Text in low-resource languages (languages with few online resources) takes many more tokens to represent, causing multiple cascading issues:

Performance degradation: Slower throughput becomes a significant issue when every sentence requires 2-3x more tokens to represent. Users get sluggish responses, and serving chats costs providers more money.

Context limitations: Longer sequences fill up the context window faster, and recall performance degrades as the model struggles to maintain coherent understanding across the inflated token sequences.

Generation quality: Token selection during generation can introduce errors. More tokens per word means more "chances to mess up" per word, potentially leading to compounding drift where small errors in token selection cascade into larger semantic failures.

Evaluating Tokenizers with Tokka-Bench

I built a tool to easily explore tokenizer performance across 100 natural languages and 20 programming languages. I started by evaluating 7 tokenizers: Gemma 3, GPT-2, GPT-4, gpt-oss, Kimi K2, Llama 3, and Qwen 3.

The project has multiple components designed for different use cases:

Open-source repository: You can clone it and run benchmarks locally. https://github.com/bgub/tokka-bench

Live dashboard: In addition to the code for running the benchmarks, I also made a live dashboard! https://tokka-bench.streamlit.app/

This allows you to easily select combinations of languages and tokenizers to compare, and switch between different metrics to understand the multifaceted nature of tokenizer performance.

Datasets and Methodology

Datasets: For evaluation, I use three high-quality datasets that represent different domains of text:

Per-language metrics: I sample 2MB of text from each dataset and tokenize it to calculate language-specific performance metrics. This approach has an important limitation: due to UTF-8 encoding differences, 2MB represents vastly different amounts of semantic content across languages. A better approach might compute a global "scaling constant" based on equivalent semantic content—for example, using parallel translations to normalize by the byte size of Harry Potter in English divided by semantic units. As it stands, cross-linguistic comparisons should be interpreted cautiously, and it's more reliable to compare different tokenizers on the same language.

Vocabulary metrics: For analyzing tokenizer vocabularies themselves, I sample 10,000 tokens randomly from each tokenizer's vocabulary and analyze their decoded properties.

Language unit definitions: Different languages structure information differently, so I define "units" for fertility and splitting metrics as follows:

- Whitespace languages: tokens per word (space-separated units)

- Character-based languages (e.g., Chinese, Japanese, Thai): tokens per character (excluding whitespace)

- Syllable-based languages (e.g., Tibetan): tokens per syllable (tsheg-separated units, with fallback methods)

Per-Language Metrics and Results

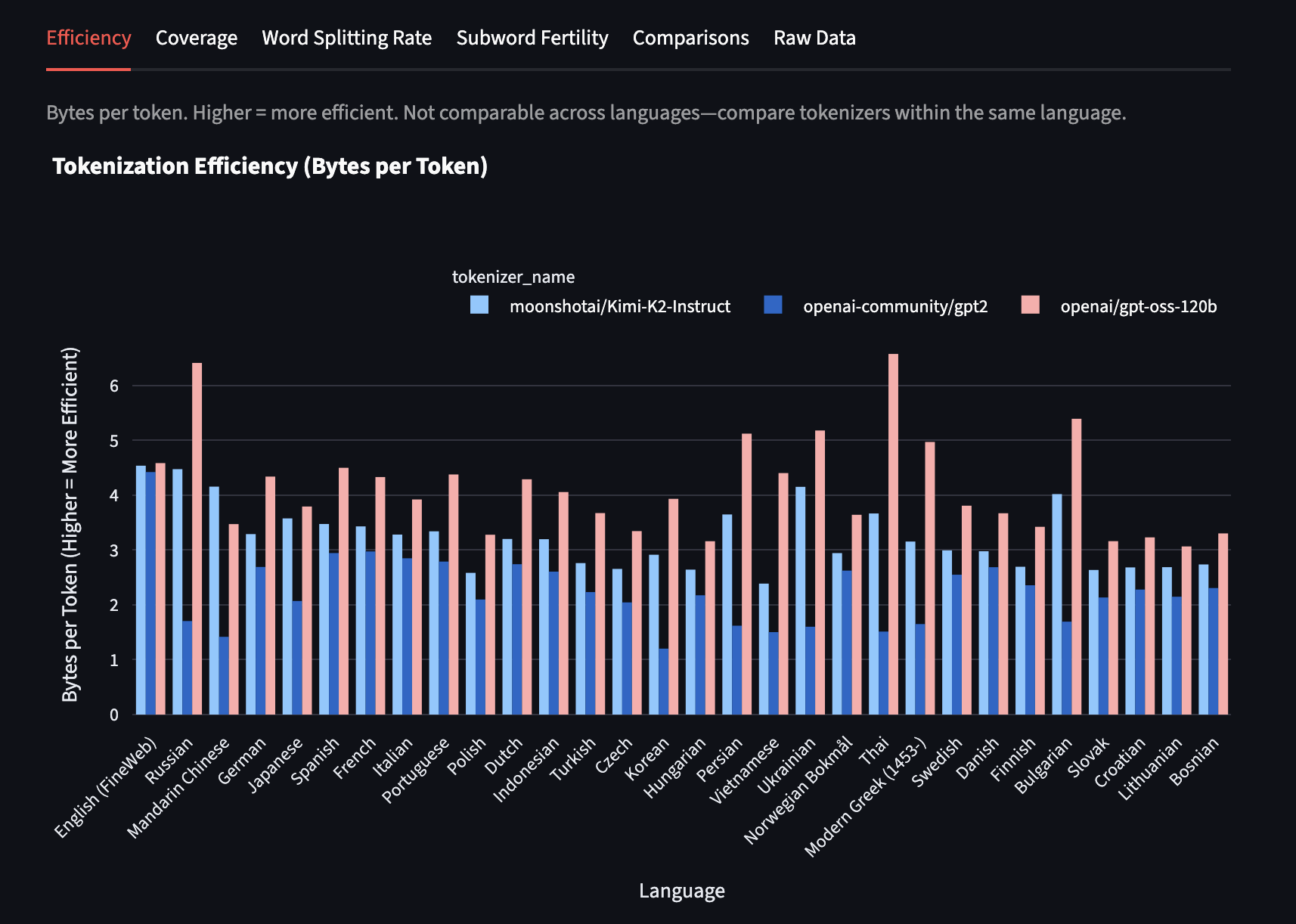

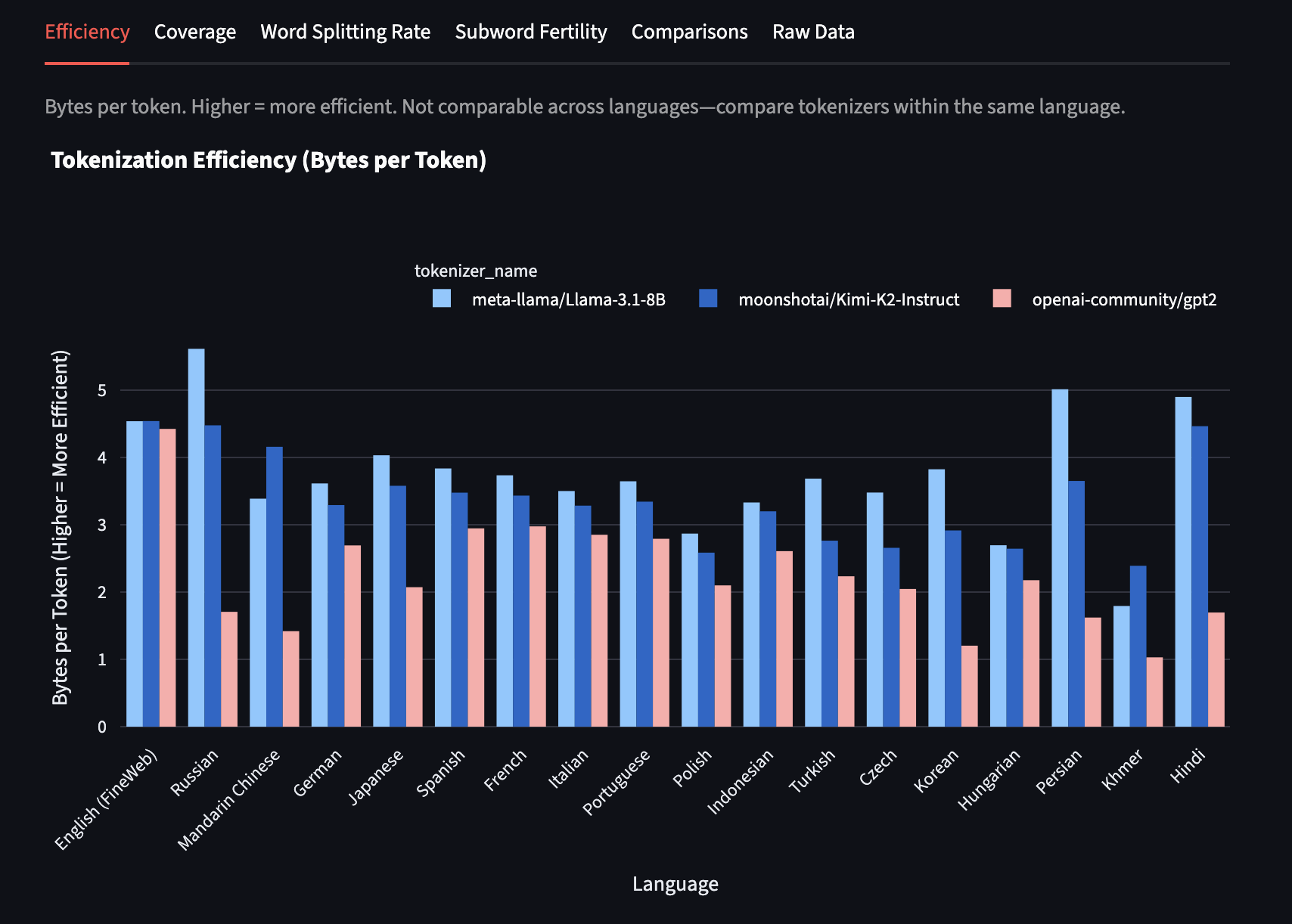

Let's compare GPT-2, Llama 3, and Kimi K2 on a subset of popular languages to illustrate the kinds of insights tokka-bench can reveal. I've chosen these three to show the evolution of tokenization approaches over time.

Context for each:

- GPT-2 has a vocab size of ~50K and was released in February 2019

- Llama 3 has a vocab size of ~128K and was released in April 2024

- Kimi K2 has a vocab size of ~164K and was released in July 2025

Efficiency (Bytes per Token)

bytes_per_token: Average UTF-8 bytes per token (total_bytes / total_tokens). Higher values indicate more efficient compression of text into tokens.

The efficiency differences reveal training priorities and data composition. Languages with higher bytes-per-token ratios are being compressed more effectively, suggesting either better vocabulary allocation or more training data for vocabulary learning.

Important limitation: This metric doesn't account for UTF-8 encoding differences across scripts. For example, Hindi achieves artificially high efficiency simply because each character requires 3 bytes to encode—allocating just 50 tokens to represent each character in the Hindi alphabet would yield 3 bytes/token efficiency. However, many Hindi characters are formed by combining consonants with vowel signs or consonant clusters, so adding tokens for these combinations (representing 6-9 bytes each) can inflate efficiency metrics while still providing poor semantic coverage. This doesn't reflect genuine semantic efficiency. The metric works best for comparing different tokenizers on the same language rather than comparing efficiency across diverse scripts.

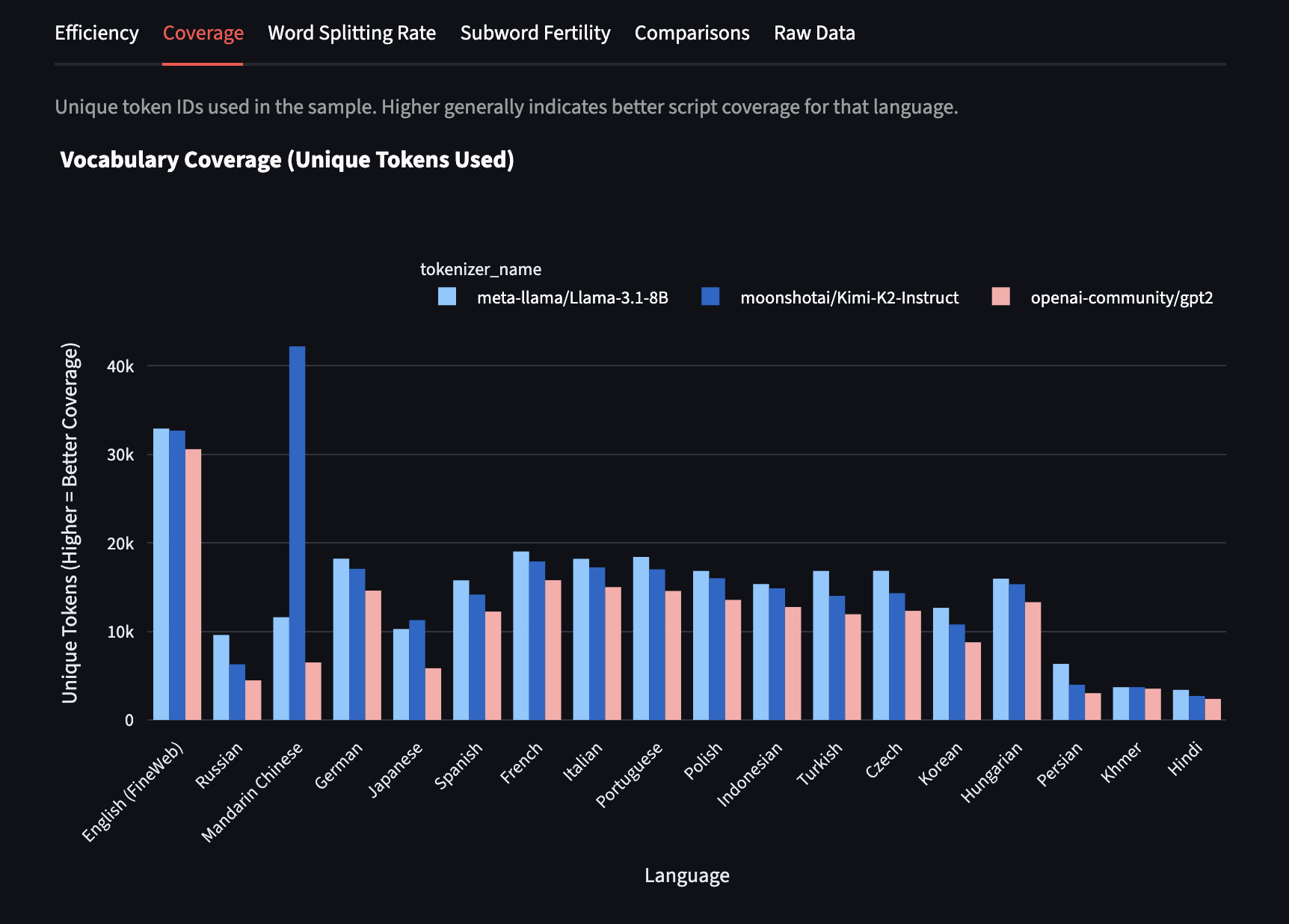

Coverage (Unique Tokens)

unique_tokens: Count of distinct token IDs used when encoding sample text in each language. Higher values suggest better coverage of that language's script(s) with fewer byte-fallbacks to individual characters.

I generally find coverage to be the most indicative of the linguistic breakdown of pretraining data. Look at how much higher the Mandarin script coverage is for Kimi K2 than the other tokenizers! This is exactly what we'd expect, since it's a Chinese LLM with vocabulary specifically optimized for Chinese text.

The coverage hierarchy reveals clear training priorities:

- Chinese has exceptional coverage in Kimi K2

- English has the best script coverage by far across all models except second-best in Kimi K2

- Latin languages (especially the Romance languages) perform well

- Other Latin alphabet languages follow

- Korean, Japanese, and Russian show moderate coverage

- Hindi, Persian, and Khmer lag significantly behind

Note on cross-linguistic comparison: Since coverage is calculated on fixed 2MB text samples, different languages requiring different numbers of UTF-8 bytes to represent equivalent semantic content makes direct comparison problematic. A more principled approach would calculate coverage as a percentage relative to a normalized baseline—but for now, the metric is most reliable for comparing different tokenizers on the same language rather than comparing coverage across diverse scripts.

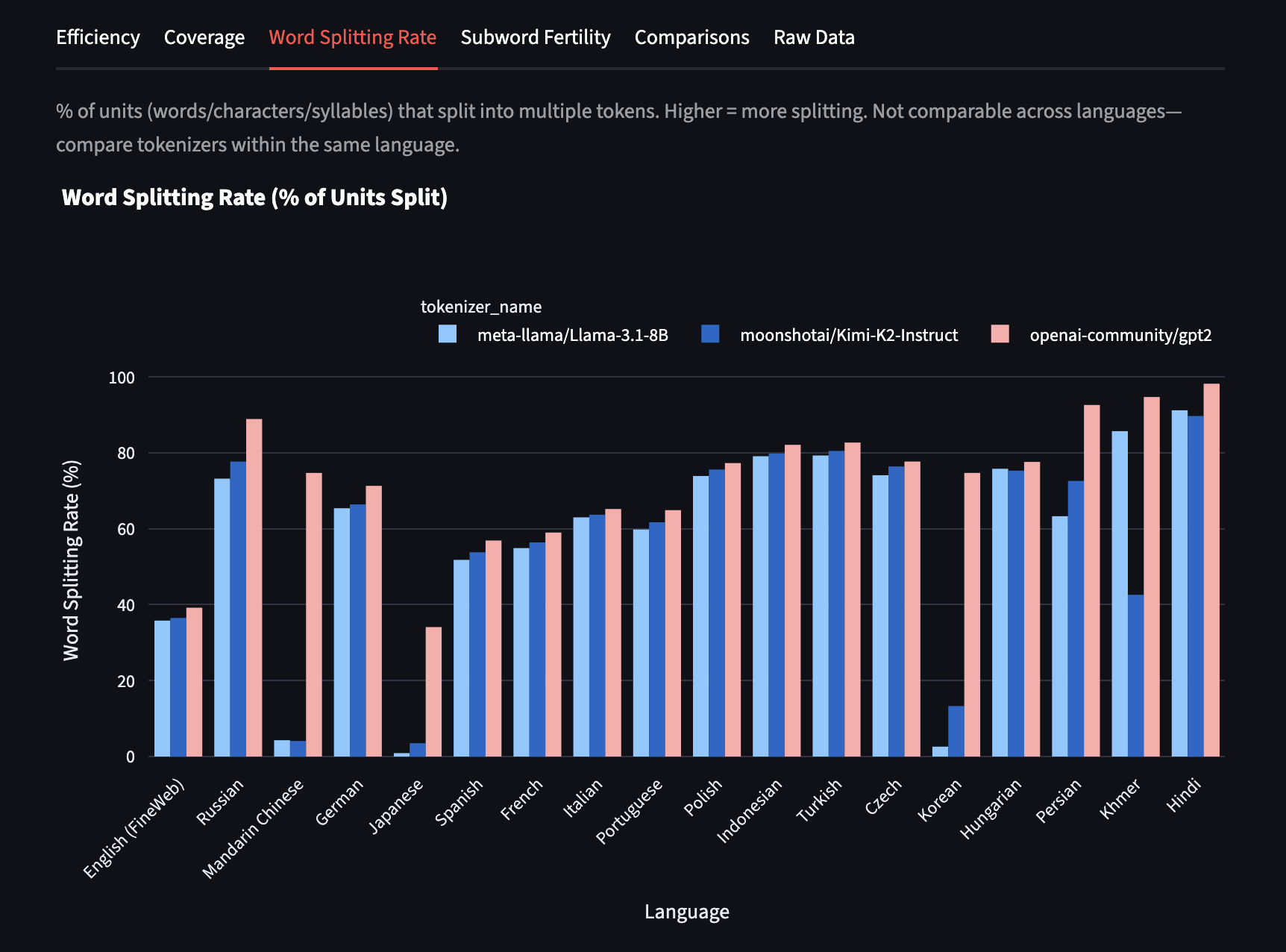

Word Splitting Rate

word_split_pct: Percentage of units that split into more than one token. Units are defined by language (words for whitespace languages, characters for character-based languages, syllables for syllable-based languages). Lower values generally indicate better alignment with natural unit boundaries.

In Mandarin, Kimi K2 has the lowest continued word rate! Only 4% of tokens are continuing a word.

Disclaimer: remember, for character-based languages like Mandarin, the metric actually measures per character, not per word. Words in Mandarin can be 1 character or more — most are actually two characters long — but that's computationally complex to determine quickly in a benchmark.

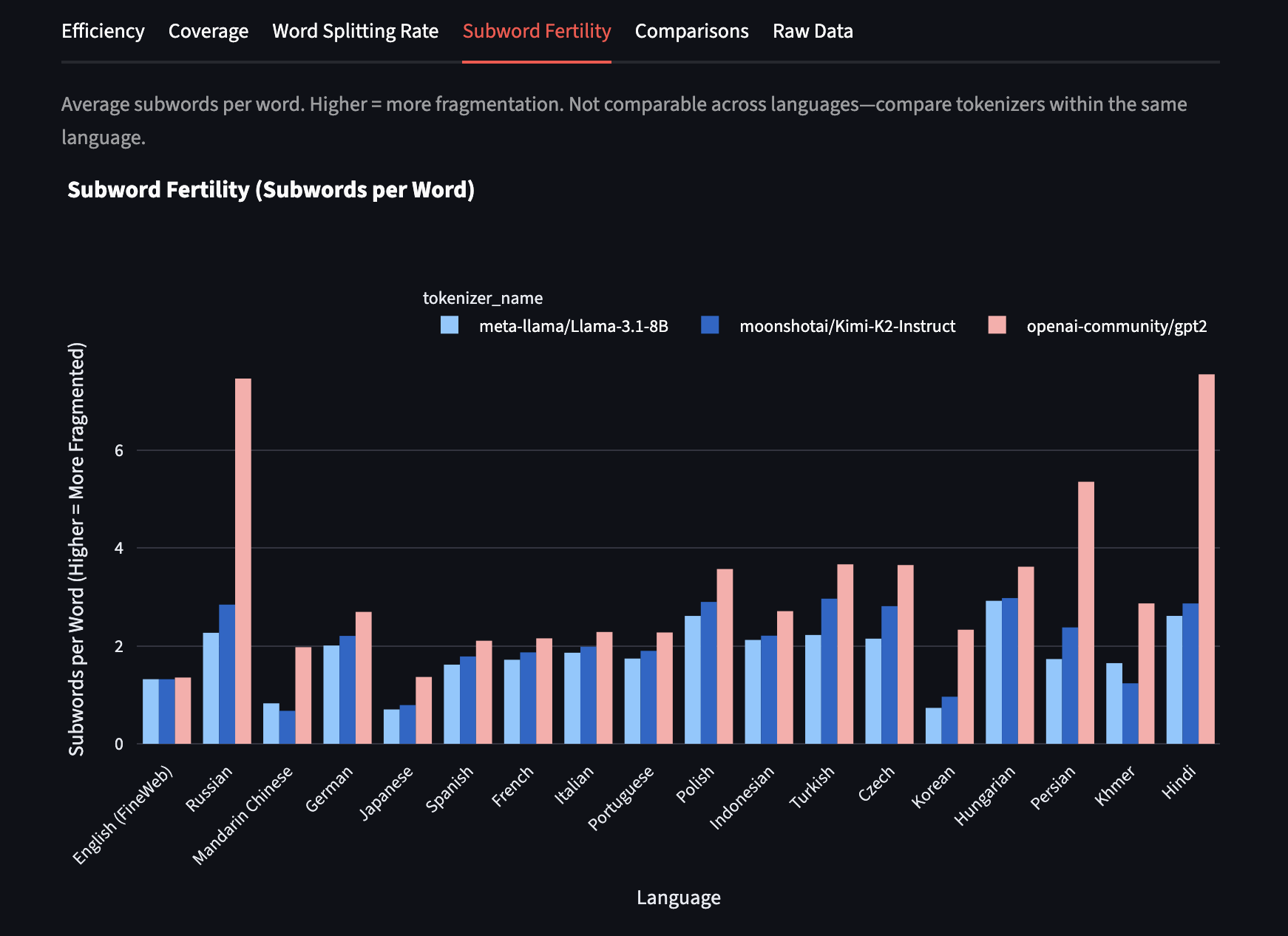

Subword Fertility

subword_fertility: Tokens per unit, where units are defined based on language structure (see methodology above). Lower values are better — closer to 1 means fewer pieces per semantic unit.

In Mandarin, Kimi K2 has the lowest subword fertility! The fertility is below 1, meaning on average each token represents more than 1 character.

Vocabulary Metrics (Aggregated across All Languages)

Calculated by sampling tokens from the tokenizer’s vocabulary, then decoding them:

tokens_starting_with_space_pct: Share of tokens that decode with a leading space. This reveals both tokenizer design (how much vocabulary is allocated to word beginnings vs. continuations) and training data characteristics (languages without spaces between words will naturally produce lower percentages).

tokens_with_whitespace_in_middle_pct: Share of tokens whose decoded text contains whitespace not at the start. Signals multi-word or whitespace-rich tokens that cross natural boundaries.

tokens_with_script_overlap_pct: Share of tokens containing characters from multiple Unicode script families. Higher values may indicate mixed-script or byte-level tokens that don't respect script boundaries.

tokens_with_{script}_unicode_pct: Distribution across scripts (e.g., Latin, Cyrillic, Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Arabic, Devanagari, Thai, Hebrew, Greek, numbers, punctuation, symbols). Shows which writing systems the tokenizer's tokens actually cover in practice.

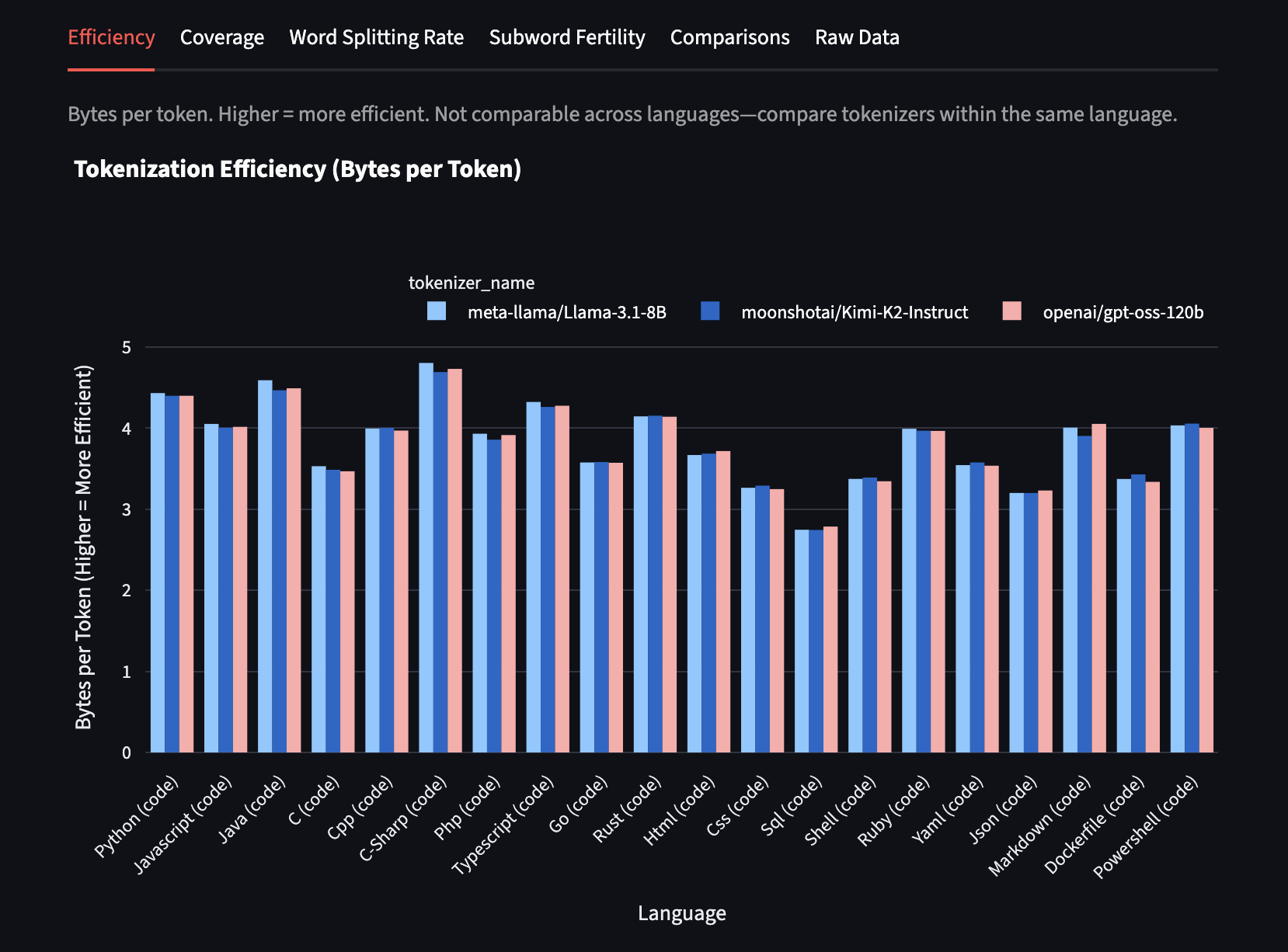

Bonus Section: Programming Languages

Finally, let's examine something interesting I noticed with programming languages (we’ll switch from GPT-2 to gpt-oss here):

There's dramatically less variation in efficiency across programming languages — Kimi K2, Llama 3, and GPT-OSS have almost identical bytes-per-token performance in each programming language!

I'm not entirely sure why this convergence happens, but I find it fascinating. It might indicate shared datasets used by all three models, or perhaps similar proportions of different coding languages in GitHub and other common training sources.

Conclusion

I hope you find tokka-bench as useful and revealing as I do! There may be some bugs lurking — I've tested a fair bit, but the tool could benefit from much more thorough community testing across diverse languages and use cases.

Please help me by contributing! Whether it's bug reports, new metrics, additional tokenizers, or expanded language coverage, community involvement will make this tool much more valuable.

If you're from an AI lab with a proprietary model but feel comfortable sharing your tokenizer's metrics for informational purposes, please reach out to me! The community would benefit enormously from understanding how state-of-the-art systems handle multilingual tokenization.

Acknowledgements and References

- Vin Howe, Sachin Raja, and Jacob Holloway reviewed my post and provided useful feedback

- Harsha Vardhan Khurdula helped me gather relevant research and think through metrics systematically

- Judit Ács was the first person (as far as I can tell) to introduce subword fertility and proportion of continuation word pieces as standard tokenization metrics in this blog post

- Rust et. al expanded on these ideas in an ACL paper that was incredibly helpful

Future Research Ideas

Performance correlation: Which matters more for downstream multilingual performance: tokenization efficiency or vocabulary coverage? The relationship isn't immediately obvious and likely varies by task type.

Optimization trade-offs: How much can you optimize coverage while maintaining efficiency? Is there a Pareto frontier we can characterize mathematically?

Predictive power: Can we predict multilingual model capabilities from tokenizer metrics alone? If so, this could provide a rapid way to assess model potential before expensive evaluation runs.